Singer believes blockchain's permissionless, decentralized, and self-sovereign nature helps eliminate some of the barriers to women’s financial inclusion in Africa.

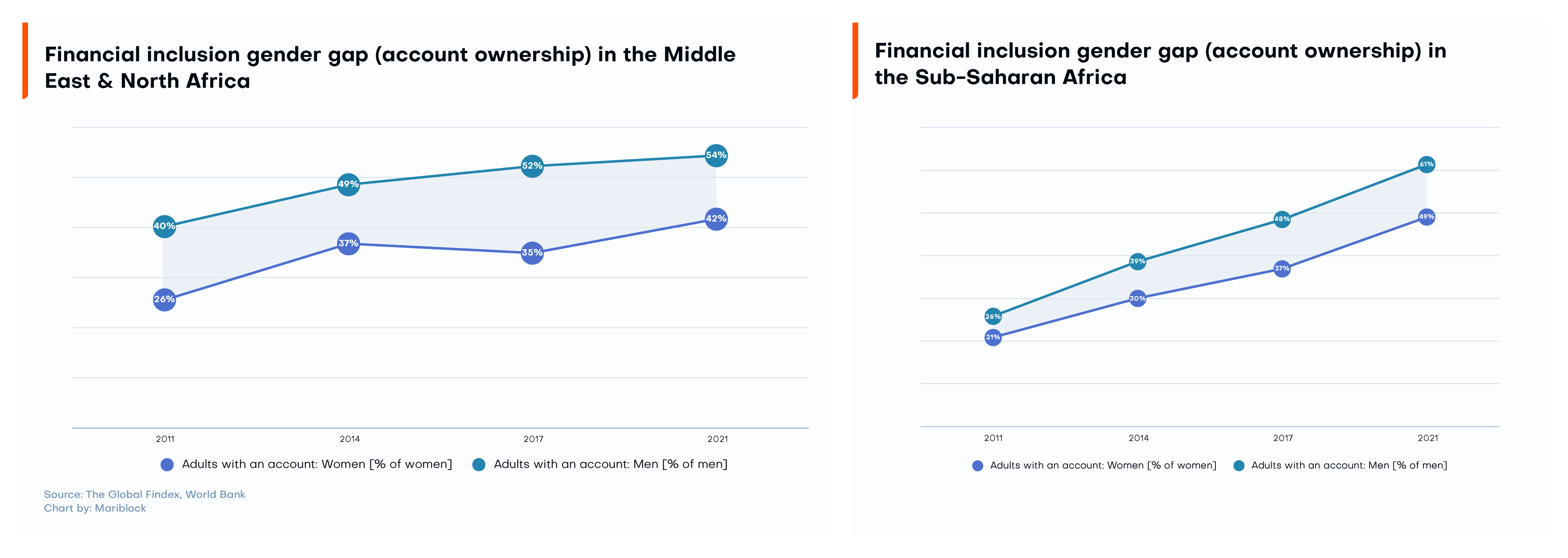

Gender inequality and financial exclusion are persistent challenges facing many developing countries, but the issue cuts deeper in Africa. One simply needs to look at the financial account ownership data in the region compared to other regions. Account ownership is considered an essential measure of financial inclusion, a gateway to most financial services.

The World Bank’s 2022 Findex report shows that the gender gap in account ownership in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region was 12 and 13 percentage points, respectively, in 2021. This is “twice as large as the developing economy average and three times larger than the global average.”

Put differently, there are 25% more men account owners in Sub-Saharan Africa than women. Put yet another way, of every 27 million people in the region, 15 million men have an account compared to 12 million women.

Using the charts below for an eye, the gap between the two genders isn’t improving.

Some factors — per the report — attributed as barriers to owning financial accounts include lack of money, socio-cultural norms, financial literacy, lack of formal education, lack of identification, and limited access to traditional financial services.

Monica Singer, the strategic advisor and lead for ConsenSys South Africa, believes that blockchain can drive financial inclusion for women by eliminating or reducing some of these barriers. She points at the permissionless nature of blockchain as a way of getting around certain socio-cultural norms, such as the belief that women must rely on their male partners or relatives for financial decisions.

“In general, women have to ask permission; we always rely on someone to give us permission … Just think about it this technology [blockchain] talks about permissionless,” said Singer. “That means that now, women, no matter where they live, no matter their cultures, can now on their own without asking permission; they can go [on] the web … and buy, sell without asking permission [from] anyone.”

Notwithstanding the persisting gender gap, account ownership in the region has been improving. It’s being driven by newer solutions like mobile money (which allows mobile network operators and their partners to offer stripped-down financial services). Mobile money is proving effective for financial inclusion partly because users’ entry requirements and associated costs are lower than formal banks.

In Niger, for instance, the Family Code “only allows women to open bank accounts to deposit funds that their husbands gave them if banks first notify the husbands.”

Singer, also an Accounting Blockchain Coalition board member, says blockchain’s design further lowers these barriers.

“So once and for all, we want to eliminate the intermediary, [and] have the blockchain, [which keeps the record of] where things go and who owns what, and gives you the freedom to choose to do whatever you want in this digital world, in the internet of value … and it’s up to women to choose to use it.

“We have left 2 billion people out of the banking system … but that’s fine. We don’t need a bank anymore. Now we can achieve financial inclusion. We can allow them to generate their own income and their own finances.”

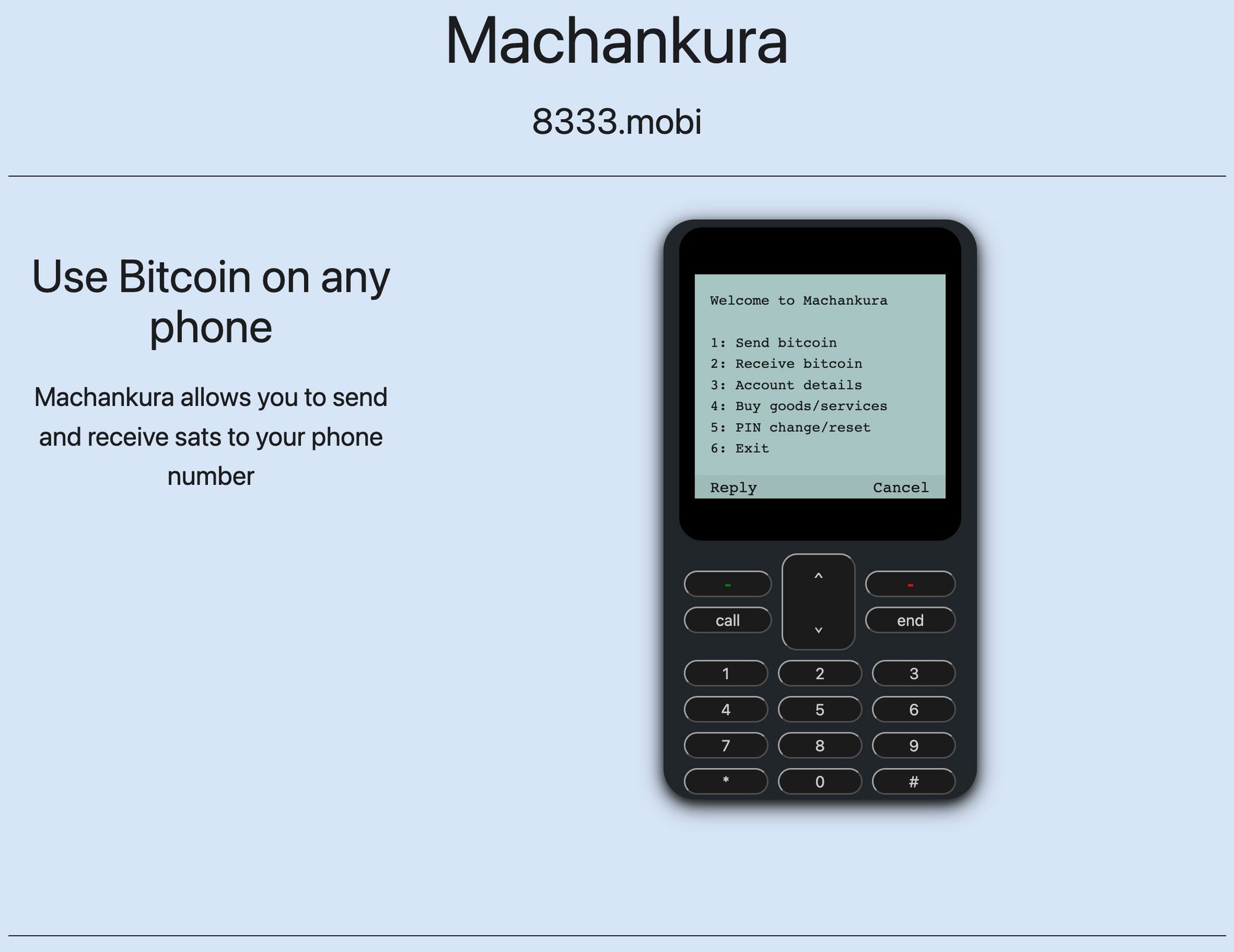

These aren’t just theoretical spewing. Africa is increasingly seeing the rise of projects building solutions that meet the African context.

Last year, Celo and Mercy Corps Venture ran a pilot project in Kenya that saw salary advance loans generated from a DeFi pool on the Celo blockchain. On- and off-ramp provider Kotani Pay disbursed the funds via the mobile money service M-Pesa.

There’s also the bitcoin project Machankura, which is essentially a bitcoin mobile money solution. For the first time, people can interact with bitcoin using their feature phones.

Yet, there’s a long way to go. Despite the rising number of blockchain-based financial services solutions, blockchain has yet to make any substantial dent in financial inclusion. Singer believes education is one of the missing ingredients. Indeed, education isn’t a challenge limited to blockchain. It remains a global issue.

To Singer, education is crucial for women’s financial inclusion in Africa. However, no one needs a fancy university degree to learn how to use blockchain. Essentially, with basic knowledge of the internet, anyone can access the global financial system using blockchain.

“I didn’t go to the university … to be a blockchain expert. I encourage women to learn the basics; they don’t have to [start with the technical part] … do you know how to send an email? Yes. That’s all you need to know … But what we need to do for the women is encourage them to feel that they can do it … you don’t need to go to a fancy university to become financially independent,” she said.

For the unconnected woman without internet access, Singer highlighted the importance of community education and emotional support groups. “In South Africa, we have the concept called Ubuntu, and it means I am because you are, and [that means] if I’m going to achieve success, I have an obligation to help others. Women that have woken up to blockchain, Web 3.0, have an obligation to go and wake someone else, and with that, we are going to slowly but surely start changing societal norms.”

Singer also addressed the lack of identification, another factor repressing women’s financial inclusion. According to a recent G20 paper, “Advancing Women’s Digital Financial Inclusion,” co-authored by the Better Than Cash Alliance, the World Bank and Women’s World Banking, one in five unbanked women cite lack of ID as one of the reasons they do not have a bank account. This is due to certain conditions in some countries, such as requirements to provide identity documentation for a related male (partner or relative).

According to Singer, blockchain prevents all these by providing self-sovereign identity for all. She said, “there are millions of people without an ID … I think it’s essential that … everybody can have an identity on the blockchain that is immutable, [and] accessible wherever you are in the world.”

Diwala and BIoT’s Hades are examples of projects using blockchain to solve the ID challenges in Africa.

The Findex report also highlighted other hindrances to financial inclusion, such as outright lack of money and distance to traditional financial institutions. While blockchain might not cure these specific issues in Africa, it presents women with power and the freedom of choice.

“It’s much bigger than gender equality; it’s what is right for society. We want to empower every individual to become self-sovereign. You control not only your money [but] your degree, your ID, your investment, your proof of ownership of property, your art, your music belongs to you, and you [can] share it when you want to.”